Jeff Wayne’s War of the Worlds and John Christopher’s Tripods

- The Time Chair

- Aug 30, 2025

- 8 min read

Between 1978 and 1984, there was a rapid transitional period which took us from the mindset of the Village People’s YMCA, to Giorgio Moroder and Phil Oakey’s,Together in Electric Dreams. Fuelled in part by advances in microelectronics and synthesisers, the metamorphosis didn’t just impact the music industry, it extended into multiple facets of society.

As we approached the end of the 1970s, there was a feeling that ‘The Future’ was happening in real-time, and that we were going to be around to witness it all unfold. It was before the time machines and hover boards of Back to the Future, and long before the World Wide Web. The Apollo space missions and Space:1999 were still fresh in our memories, and we were confident that if we could just find the right discarded TV set with its vacuum tubes still intact, then our street’s very own space programme might be possible. Seriously. Our parents set boundaries around our house beyond which we could not venture, so any projects or world-conquering ventures were limited to approximately one square mile. The rest of the planet never existed, and this limitation encouraged focus.

The technical foundations were in place. I had my own miniature tool kit which my dad kept supplied with tools he no longer used for work. Every week or so he’d bring home a device of some description from one of the old houses he’d been working on which I would spend a couple of hours taking apart to find out what is was and how it worked. I can’t remember the amount of times I nearly broke my fingers whilst dismantling a mechanical clock with its primary spring coil still fully wound. The energy released by some of those buggers if you turned the wrong screw at the wrong time taught me more about science in two seconds than a whole year at school did. Whether or not a clockwork spacecraft is possible is still up for debate, but back then, springs, coils and levers were at the heart of our technologies.The Terminator used pistons and levers, as did the AT-AT and Walkers in The Empire Strikes Back. Microchips at the time were more of a curiosity than a necessity, and you only needed to lift the hood of a video cassette recorder to realise that they weren't really required.

This post begins in the late 1970s. Art Garfunkel’s Bright Eyes ruled the charts causing harrowing flashbacks to the animated film, Watership Down. Cliff Richard and Abba still looked young, and Pink Floyd were causing a long-overdue ruckus in British schools with the release of Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2.

Early one Saturday morning before the rest of the street was awake, for some reason or another my brother had to call round to his friend’s house who lived in the next street. Apparently, there was going to be a reveal of something special which his friend had managed to get hold of. Back then, new items or purchases were very rare, so if someone got hold of something new, it was a big deal. When my brother’s friend opened his front door, the delight on his face was as clear as day. We entered his front room, and I immediately spotted the game Rebound in the middle of the floor. I’d never played it before but had seen pictures of it in catalogues. I was fascinated by its simplicity, and after only a couple of rounds of play became hooked. My brother and his friend seemed very happy for me (an obvious ruse to keep me distracted whilst they walked tentatively to the table in the far corner of the room).

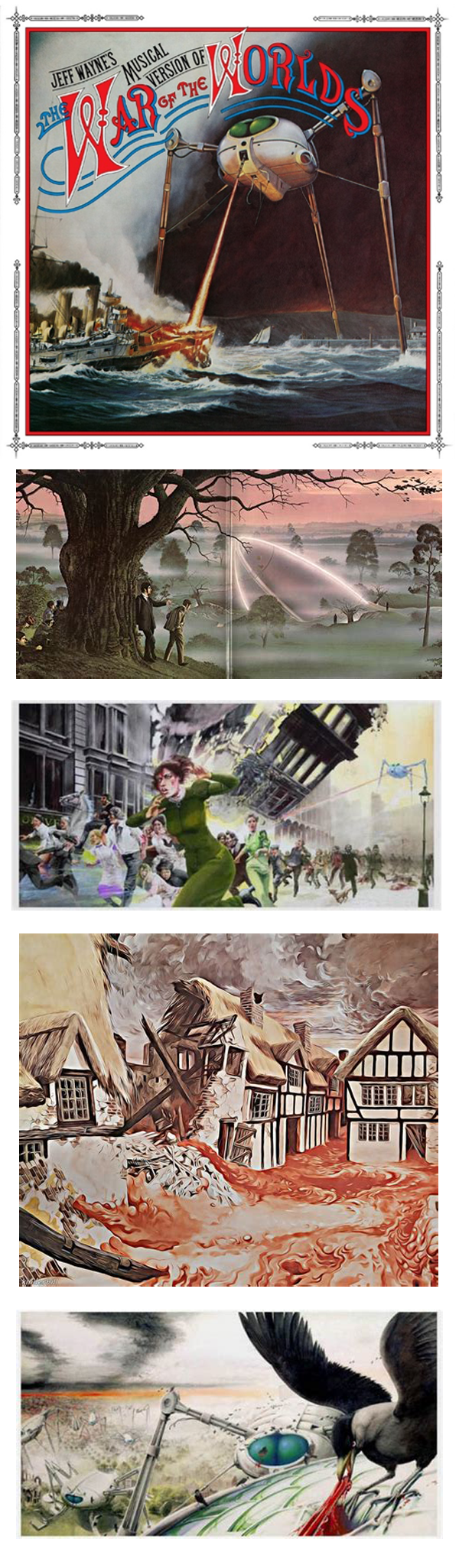

After a few more attempts at scoring 300 on Rebound, I heard my brother say, “Wow” in an exasperated tone whilst he was looking at something on the table. Curious as to what had caused his reaction, I went to take a look. Laid out in what seemed like a very delicately arranged grid, was the double album and all associated artwork from Jeff Wayne’s musical version of War of the Worlds. It looked incredible. I’d seen repeats of the 1950s film version with its flying saucers and red death rays on TV, but the front cover of Jeff Wayne’s musical version was something quite different.

Extending what seemed like 100-feet into the air, was a huge metallic tripod. For a while I was a bit confused by the image because although I was very young, I knew that tripods had three legs, but the front cover seemed to depict one with four. It was only after I listened to the record and looked at the cover again that I realised that the fourth leg was in fact the Tripod’s heat ray striking the ill-fated Thunder Child ship (and not a metallic foot stomping through its deck).

It was easy to see why my brother and his friend were so excited. Prog Rock was still a thing in the late 1970s, and this album with its incredible accompanying artwork embraced the genre perfectly. What made things even more exciting is that my brother’s friend said we could borrow the album for a few days. This gave us ample opportunity to pour through the illustrations in detail (and make a sneaky cassette recording of the record). Sides one and two were called: ‘The Coming of the Martians’, and sides three and four were: ‘The Earth Under the Martians’. The sleeve featured paintings from artists John Pasche, Geoff Taylor, Mike Trim and Peter Goodfellow, and they were astonishing. Of all the illustrations included, the one which stood out for me the most was, ‘Brave New World’, a depiction of an underground city where humans could survive the tripods and preserve mankind. In the story, the Artillery Man (David Essex) had already made a start digging it.

“We'll build shops and hospitals and barracks right under their noses - right under their feet! Everything we need - banks, prisons and schools...We'll send scouting parties to collect books and stuff, and men like you'll teach the kids. Not poems and rubbish - science, so we can get everything working. We'll build villages and towns and... and...we'll play each other at cricket! Listen, maybe one day we'll capture a Fighting Machine, eh? Learn how to make 'em ourselves and then wallop! Our turn to do some wiping out! Whoosh with our Heat Ray - Whoosh! And them running and dying, beaten at their own game. Man on top again!”

The idea that a cavern of such magnitude could be dug manually by a few people with buckets, spades and pickaxes didn’t bother me at the time. It wasn’t a case of me suspending my disbelief; I simply believed that anything was possible if we had enough time to do it. I was also mesmerised by the steam train powering across the upper third of the image. It was futuristic, Art Deco, and yet good old Victorian engineering was still at the heart of transport.

Wayne’s version of War of the Worlds made a big impact where I was brought up. So incredible was its production value that it still sounds astonishing to this day. It also contained one of my favourite songs from the 1970’s, Forever Autumn, sung by Justin Hayward. There’s something special about songs produced in the late 1970s in that during the early transition from analogue to electronic, the combination of traditional instruments and synthesisers created a unique sound which seemed other-worldly, yet familiar. Think ELO and Pink Floyd.

As we left the 1970s and steamed headlong into the New Romanticism of the 1980s, the heavy makeup and synthesisers didn’t quell the possibility of an alien invasion from Mars. If anything, they amplified it. You only had to look at Gary Newman, Bowie, Japan or Visage to work that one out. When synthesisers became more mainstream, we were able to create sounds that we had literally never heard before, and there was no shortage of singers and bands whose image seemed to be completely off planet.

Something similar was also happening with televisual special effects and technology in general, so by the time the BBC released its TV adaptation of John Christopher’s The Tripods in September 1984, there had already been more than 10 space shuttle missions, and although the storylines of War of the Worlds and The Tripods were very different, the terrifying Tripod imagery had already been well-established in the minds of many.

John Christopher's The Tripods

Set in 2089, the opening scene of The Tripods portrays a dystopian version of England which, following some sort of cataclysm or societal reset, has technologically regressed by what seems like centuries. Blacksmiths, village fates and horse and carriages greet us, and interactions between characters seem quaint and Victorianesque. The picturesque scenery of the opening location grates awkwardly against the high-tech opening credit sequence and foreboding soundtrack. You knew from the start that something wasn't right.

When I first saw the opening title sequence, I was taken aback by the 3D graphics. I was really into computing at the time, and in 1984 we were on the threshold of being able to create crisp 3D graphics on-screen. The fly-though combined with the ominous soundtrack had me hooked instantly.

After the initial characters are established, the arrival of the cause of our suspicions reveals itself in the form of an 80-feet tall metallic tripod, which resonated with Jeff Wayne's War of the Worlds far more than it did the 1953 film version. Green and blue screen technology for television was in its infancy back then, but the BBC had really pulled out all the stops. Blue Peter even put together a segment explaining in detail how the special effects were achieved which added to The Tripod's quickly-rising viewing figures.

As episode one progressed, it instilled fear and hope in equal measure. There was clearly an imperialist undertone to the saga, as well as the classic hero's journey narrative, but the thing which troubled me the most was the idea of Capping when children reached the age of 16. At the time I interpreted the idea literally, but in later years saw it as a metaphor as to the mind controlling capabilities of television, the education system (and more recently) social media.

Pink Floyd had fired a warning shot across the bow a few years earlier with Another Brick in the Wall, but at least school was temporary and you could undo some of the damage later on down the line when you got a bit of life experience. But not with Capping. Similar in sentiment to One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, having your brain physically and permanently altered exudes a powerful dose of The Uncanny, and as a young, carefree child, you would do everything in your power to prevent any such assault.

At the time, BBC programme creators cared very much about their audience, and its overall position sided largely with the good guys. The Tripods were the overlords, but the courage, will and imagination of just a handful of young people could eventually take them down given enough time. The human spirit was portrayed as an uncrushable force which always found a way.

As the Tripods played out, it encouraged me and many of my friends to think about how we would fight the good fight were we ever to find ourselves under attack from a group of power-crazed overlords, which is a much better mindset than simply rolling over and submitting because we’d been provided with enough bread and circuses (Fast food and entertainment) to keep us bickering amongst ourselves.

The spirit of defiance and rebellion was widespread throughout the 1970s and 1980s, which is part of the reason why Gen Xers seem so direct and insolent in comparison to the generations that followed. We had obligations and responsibilities; not privileges and entitlement. Both Jeff Wayne’s War of the Worlds and The Tripods were part of a wider swathe of programmes that pitted good against evil, and whereas evil was initially portrayed as all-powerful and undefeatable, good eventually prevailed against the odds. How things have changed.

Comments