Double Science

- The Time Chair

- Aug 26, 2025

- 5 min read

Double Science on Friday afternoon in late July, 1989 was the only time I ever fell asleep in school. Now this wasn't because of a disinterest in the subject, it was because on this occasion, the science department television had been wheeled in to the lab to show us Nick Park's Grand Day Out.

The lesson was supposed to be about gravity, and I suspect the teacher had watched the animation, saw that it had something to do with the Moon, and made a tentative connection to the topic which would give him the afternoon off before the weekend.

The science lab was hot and the work bench I was sat at was bathed in one of those 1980s, early afternoon, Summer Suns. You remember the type. The ones which slowly but comfortably put you into a slumber where you phased in and out of consciousness. It wasn't too hot nor cold, it was just right. A true Goldilocks 80s summer Sun. Fortunately, I woke up a few seconds before the final bell rang, like one of those dreams where you hear the alarm ring, wake up, and after a couple of seconds the awake world alarm rings. Time dilation at its best.

Ordinarily, science lessons were exciting and packed with experiments that often went wrong. You might recall the magnesium or potassium combined with water demonstrations, or the igniting of a hydrogen bubble with a smouldering wooden taper. For a brief period during the late 80s, myself and a few classmates had developed a fascination for science experiments, but they often fell outside of the National Curriculum.

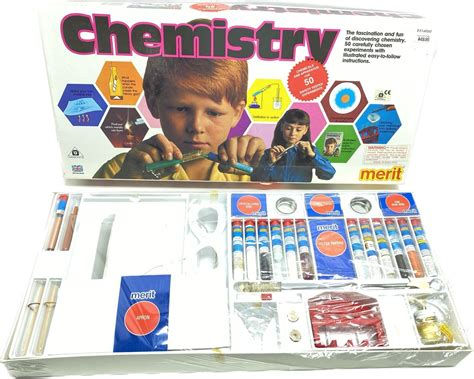

In 1988, one of the most popular Christmas presents was a Chemistry set. Depending on how much your parents could afford, the sets came in 25, 50 and 100 pieces. I got the 50 piece set that year, and quickly used up the methylated spirits which came with it creating some peculiar dye which I subsequently stained the carpet, my thumb, and index finger purple with for a week.

A side product of the Chemistry sets was that we started taking a greater interest in the subject at school. Early one Monday morning, we entered the science lab as usual and my friend and I took our usual places behind the benches at the back of the room. The lab layout was how you probably remember it. Each bench had its own power sockets and clusters of four small gas taps built into them. The gas taps were used to fuel Bunsen Burners via 12-inches or so of rubber tubing. Prior to any experimentation, the teacher would vanish into a mysterious side-room to turn the lab gas supply on, and switch it off at the end of the lesson.

On this particular morning , there didn't appear to be any practical experiments planned, but I twirled one of the four gas taps anyway. To my surprise, some gas came out. Basically, whoever had used the lab last hadn't turned the main supply off.

Now also at our school that year, there was for a brief time a trend surrounding the gelatine sweet known as the, Jelly Teddy. In brief, if you licked a Jelly Teddy, and rolled it between your hands for 20-seconds or so, it would become very tacky. You would then wait for the teacher to turn their back, and throw the teddy vertically upwards at the ceiling tiles. Provided the tackiness was just right (we were experts at judging this) the teddy would stick to the ceiling pretty much indefinitely. When someone in class launched the first successful "Ceiling Soldier", others would join in, and as the lesson progressed, an army of upside down jelly teddies would slowly make their way across the ceiling towards the front of the class.

After confirming one more time that my gas taps were indeed active, I looked up at the ceiling and noticed that a jelly teddy march had commenced from somewhere in the middle of the lab ceiling. There were perhaps 4 or 5 already in place in a rather impressive straight-ish line headed towards the blackboard. The teacher at the time was quite a naive chap who faced the blackboard far more than he should have given the 'challenging' nature of our class. We were regularly on something called "Report Book", which was a general record of the class's behaviour which had to be recorded and signed by each teacher at the end of the lesson. This was a bigger deal than a "Report Card", which was an individual record usually handed to the duffers or the class trouble-makers.

Now amongst the side projects that me and my fellow Chemistry set recipients had devised that year, was a flame thrower. It was common knowledge that some cans of deodorant used butane gas or CFC propellant back then, and that simply spraying a lit match with it would provide a basic (but still dangerous) deterrent to the uninitiated. However, 1989 also happened to be the year when home brew wine and beer-making kits became widely popular amongst the public in the UK, and these kits often included a 10-litre glass bell jar with a large cork. It was only a matter of time before I worked out that one of these jars could be filled and compressed with deodorant and deliver a shockingly more powerful version of a flame thrower. In fact, during the testing phase of one such device, a friend of mine didn't put the cork in securely, and it popped out mid-flame releasing the propellent all in one go. It took about 3-weeks for his eyebrows to fully grow back, but taught me more about gases and pressure in 30-seconds than an entire year in science class did.

After glancing once more at the growing jelly teddy army on the ceiling and back towards the four gas taps on the the lab bench, an horrific idea came to mind, one which to this day rates on that special scale that many of us Gen Xers keep. The, "How the hell did I not die multiple times during my childhood?" scale.

Without expecting any joy, I tried to open one of the cupboards within reach of my bench to see if there was any equipment in it, but it was locked. The locks back then were very basic, and after finding a paper clip, it took me about 10 seconds to pick it. In the cupboard were multiple lengths of rubber tubing, Bunsen Burners, Gauses, Asbestos mats, and Tripods. The Full Monty. There was even a lighter and some thin wooden tapers.

As the lesson progressed, I noticed that the teacher was turning his back on the class quite a lot, and after a while I recognised that there was a pattern to it. For every 10-seconds or so he was facing us, there would be a 20-second period when he would be writing on the board. As slowly as I could, I took four rubber tubes out of the cupboard next to me, connected them to the four gas taps and clamped them together in my left hand. After checking the timing of the teacher's turns once more, I quickly turned all four taps on and sparked the lighter.

In an instant, a six-feet-high column of flame jettisoned out of the tubes and hit the ceiling before licking its way across the tiles towards the front of the lab. The room lit up with a sunrise yellow and the shadows of multiple heads appeared across the wall at the the front of the lab.

I immediately turned the taps off as quickly as I'd turned them on. At that precise moment the flames vanished, and every head in the room, including the teacher's, turned to look in my direction. My hands were calmly on the lab bench and there were no gas tubes in sight. After another brief moment, I slowly tilted my head upwards and frowned at the sight of twenty or so smouldering Jelly Teddies.

Their mission had failed.

Comments